Above: Photo by Shaunl, iStock / Getty Images Plus

Economics Professor Robert Fairlie has been making national headlines for his alarming report showing a 41 percent drop-off in the number of active Black business owners from February to April. —Photo by Melissa DeWitte

If you’ve strolled down the Main Street of any town or city in the United States lately, one thing becomes very clear: The COVID-19 pandemic is decimating the country’s small businesses.

What may not be quite so obvious from observing empty storefronts and going-out-of-business signs is that African American/Black entrepreneurs are taking the hardest knocks, according to UC Santa Cruz Economics Professor Robert Fairlie.

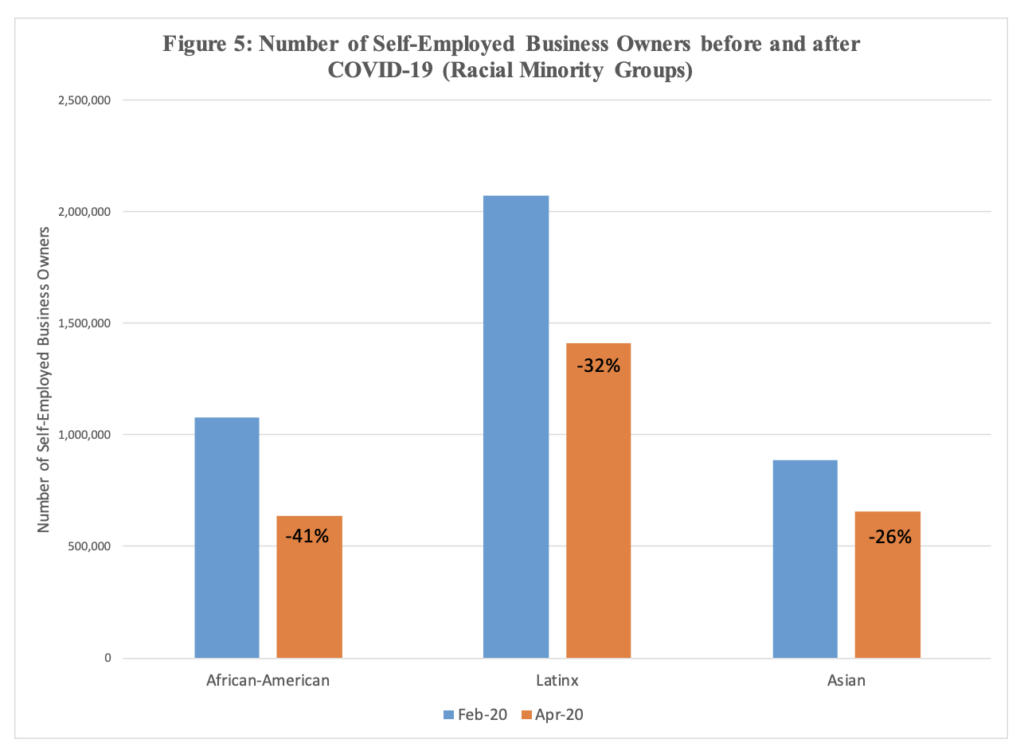

Latinx-, Asian American–, immigrant-, and female-owned businesses are also suffering. But Fairlie has been making national headlines for his alarming report showing a 41 percent drop-off in the number of active Black business owners from February to April, when the number decreased from 1.1 million to 640,000.

In recent months, immigrant-owned businesses have decreased by 36 percent. Latinx business ownership fell by 32 percent, and Asian American business ownership dropped by 26 percent. Female ownership has also taken a disproportionate hit, with a decrease of about 25 percent. In comparison, the drop-off for white-owned businesses in the same time frame was 19 percent.

“I’m very concerned about a permanent drop-off of these businesses,” said Fairlie, whose research is based on statistics from the Bureau of Labor Statistics and the U.S. Census Bureau. “I think that policymakers, as they hear more about it, will become more and more worried.”

Many of those shuttered businesses have less than a month of cash on hand and can’t easily take on loans. And while many of these businesses enjoyed a slight rebound bump in May and again in June, when many states eased lockdown restrictions, Fairlie said that modest recovery obscures a more complicated reality: Though many businesses tried to reopen, they still faced the same expenses and, in many cases, enormous drops in revenue, with many consumers reluctant to patronize businesses because of safety concerns.

Change through policy

Fairlie has been getting the word out about this crisis to the widest audience possible. So far, the Washington Post, New York Times, CBS, PBS, Wall Street Journal, USA Today, Bloomberg, BBC, Forbes, and Vox have quoted his research extensively.

But his biggest priority is policy change to address the wealth gap in the United States. The U.S. Senate Committee on Small Business and Entrepreneurship has cited Fairlie’s work in its testimony regarding the problems minority business owners face during the epidemic. He also advised the Congressional Oversight Commission, which oversees the CARES Act programs established and administered by the Treasury Department and Federal Reserve. The commission is interested in ensuring racial equity in their programs and asked him to help.

A graphic from Prof. Fairlie’s abstract, “The Impact of COVID-19 on Small Business Owners: Evidence of Early-Stage Losses from the April 2020 Current Population Survey.”

Fairlie’s research has also inspired potential new federal legislation. Concerned with the findings in Fairlie’s report, a group of U.S. senators including minority leader Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.), Cory Booker (D-N.J.), and vice presidential candidate Kamala Harris (D-Calif.) introduced a bill this past summer that would increase resources and funding for minority-owned businesses hurt by COVID-19. The bill would increase funding for the Minority Business Development Agency, which is part of the U.S. Department of Commerce, increasing its ability to write grants in support of small businesses.

Tragic timing

While all business closures are cause for concern, the timing of the African American/Black business downturn is especially troubling. There has been widespread press coverage, including a recent New York Times report, calling attention to a bitter irony: many African American/Black business owners are being pushed to the brink while African American/Black communities have suffered most of the burden of a public health emergency, in addition to undergoing continued disproportionate levels of police brutality.

“Black people are more than twice as likely as other Americans to die of the coronavirus and much more likely to be victims of police violence,” according to the Times report.

And the latest downturn follows a report, published by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, stating that more than a third of African American/Black–owned businesses were already “at-risk” even in 2019. Even more troubling is the fact that the shuttering of those businesses contributed to Black unemployment.

Not all of the currently inactive businesses are permanently closed, Fairlie noted.

“It could be that the owners decided to not work in the business for a couple of months while we get through shelter-in-place restrictions and other things,” Fairlie said. “It could be that they closed for good. There’s just no way to know that yet.”

But business owners who have been forced to close up shop temporarily may find it difficult to rebound, Fairlie said; shutting one’s doors doesn’t put an end to obligations and bills.

If those enterprises close, the loss will decrease the appeal and vitality of business districts all over the country. The end result could be a dramatic rise in racial inequality in the United States, with decreased opportunities for economic advancement, job creation, and longer-term prosperity.

Will some of those businesses return when restrictions lift and the country has a better handle on a pandemic that has claimed more than 200,000 lives?

“Many will try to restart, and many, unfortunately, will fail—not just Black-owned businesses, but everyone,” Fairlie said.

Getting to the root of the problem

To address the crisis facing minority-owned small businesses, it is important to delve into the nature of the problem, Fairlie said. One major factor is their modest size. Mom-and-pops can’t take on loans as easily as larger businesses, and have more difficulty competing for contracts for that reason.

And many of these modest-sized operations haven’t been able to pivot quickly from in-store traffic to online platforms.

Another factor is the type of these small businesses.

“Many are personal services, such as barbershops, nail salons, laundry services, cleaning services, and a lot of those things got hit very hard,” Fairlie said. “Retail also took a major hit. The one industry that did not get hit was agriculture, which makes sense. But if you look at agriculture as an industry in the U.S., the businesses are mostly white-owned. There are a lot of Latinx workers, but not owners.”

Asian American–owned businesses tend to focus on certain industries such as restaurants and personal services such as nail salons and barbershops.

Fairlie said that Americans can witness the disproportionate impacts on small businesses just by cruising through their own business districts. During the first initial lockdown order in California, Fairlie was driving down Mission Street in Santa Cruz.

“I don’t remember the big fast-food outlets ever being closed,” he said. “I remember seeing big huge signs saying, ‘We’re open. Our drive-through is open.’ But a lot of the little restaurants had closed down.”

“Think of a small barbershop,” he said. “How much red tape do they need to figure out to open again? If it’s a larger chain, corporate is telling them, ‘Here is what you need to do. Follow these steps, and you’re fine.’’’

Stepping up to support businesses

In the face of this ongoing crisis, communities have been asking themselves: What can be done to support minority business owners in the face of such an intractable problem? How can loyal customers step up and help them survive, and how can social media platforms bring them more exposure?

Perhaps a widespread awareness of these businesses and their precarious futures can lead to broader community support—and this outpouring of help is already starting.

For example, some African American/Black–owned enterprises started to see a spike in business in the wake of the George Floyd killing and the ensuing protests.

“Consumers have blanketed the internet with hashtags—#BuyBlack and #BuyBlackOwned—and with lists of Black-owned businesses to support,” Mother Jones magazine reported in early July.

“In addition to the Black-owned businesses lists, apps that direct users to Black-owned companies have seen download spikes, while tech companies, from Yelp to Uber Eats, have created tools to allow users to search for Black-owned businesses,” the magazine reported.

Meanwhile, many of these small-business owners, or at least those who can afford it, are being proactive—revamping operations, switching up marketing techniques, and investing in e-commerce as a way to expand their online presence and weather the crisis, according to a Chicago Tribune report.

Fairlie believes that community support of local businesses is crucial, but that sweeping policy changes must also be made to address this inequity. Earlier this year, California Governor Gavin Newsom’s office contacted Fairlie, hoping to find out how minority-owned businesses were faring in this state compared to the national average.

Fairlie generated those numbers, and with sobering results: “The drop in business activity was even higher here because California was one of the leaders in imposing health restrictions,” making it more difficult to do business than in states with more lenient policies toward COVID-19, Fairlie said. “There were important health reasons for shutting down, but the shutdown had a disproportionate impact on minority businesses.”

Helping mom-and-pop go high tech

Jacob Martinez (Oakes ’04, evolutionary biology) founded Digital NEST, a hip technology learning center in Watsonville designed to help young people from rural areas master high-tech skills. —Photo by Carolyn Lagattuta

Others have been harnessing the power of tech to help businesses in need.

Jacob Martinez (Oakes ’04, evolutionary biology), executive director of Digital NEST, an innovative Watsonville-based nonprofit that provides immersive tech experience for young people in rural areas, said that communities that want to help these businesses thrive and survive can offer technical advice and online platforms to help them retain customers and find new ones through broader exposure.

Early in the pandemic, many local businesses owned by Latinx and immigrant entrepreneurs reached out to Digital NEST and asked for help. Many small restaurants in Watsonville and Santa Cruz were struggling because they could not pivot quickly to a takeout-only format.

“In order for those businesses to do this successfully, they needed some kind of online presence,” Martinez said. “Most don’t have websites or good logos. Many aren’t even listed on Yelp.”

If these businesses had deep pockets, they could pay big money to hire someone to build an eye-catching interactive website and help them with search optimization, Martinez said.

“But in communities like Watsonville, with small businesses, it is just not realistic for many of them to enter the 21st-century digital world or have the resources to pay someone to do that,” Martinez said.

To help these businesses, Digital NEST partnered with a local tech company, Bees2Biz, to launch an easy-to-use online business directory called at831.org that allows visitors to browse through categories of local businesses—from takeout food to home improvement to optometry services, and many more. The online directory includes a list of hand-picked recommendations and detailed instructions for businesses that wish to be featured on the site.

“We have nearly 200 businesses on the site now, so this is a really big deal for small communities like Watsonville and Salinas,” he said. “We’ve been getting so much traction for at831.org that we’re thinking of adding e-commerce for businesses and support services.”

Martinez said that the city governments of small towns should factor in these family-owned businesses when considering their communities’ post–COVID-19 recovery needs. Supporting those businesses is not just a question of preserving the liveliness and character of downtown areas. It’s also a way to stop more families from being displaced.

“What happens to these families if these businesses go under?” Martinez said. “Do they leave? I am really worried about this, with all these big tech companies,” Martinez said, noting that the pandemic has underscored the reality that tech workers can often work remotely.

“They don’t need to live in San Francisco or the Bay Area. They can work wherever they want,” he said. “The loss of local businesses and families creates openings for more affluent citizens to move in and afford a home. If that happens, what kinds of businesses will change downtown? Will we see the community shift economically through gentrification?”

Support from the digital public

Like Martinez, Fairlie believes that online communities can step up to help businesses.

“I think there is a lot of value to that,” he said. “A lot of consumers have been going on Instagram, saying, ‘Here is a list of Black-owned neighborhood businesses. Follow them on Instagram. Go eat at this restaurant. Go to these stores. Support these businesses. It is extremely valuable.”

Fairlie also mentioned the importance of mentorship programs, in which experienced business owners help newer ones find their footing. Meanwhile, direct assistance to small businesses, including the work of private foundations, has contributed to relief efforts. One of the first examples was former NBA all-star Magic Johnson’s announcement that he would provide $100 million for small-scale businesses owned by women and underrepresented groups.

As the crisis continues, Fairlie will keep tracking the numbers of businesses owned by minorities to see how they are faring. He also hopes to have more follow-up talks with the Senate committee. And he emphasizes that the threat to minority-owned small businesses should be a matter of concern to all Americans.

While all small businesses are facing major setbacks right now, Fairlie said that people should be especially concerned with minority-owned small businesses because they are the ones that are hurting the most.

He’s also wary of a domino effect; the collapse of these businesses widens the racial wealth gap, and decreases opportunities for minorities who have gotten jobs at minority-owned businesses. He pointed out that African American/Black–owned businesses, for example, tend to hire African American/Black workers. The absence of those businesses also stifles the economy.

“It’s hard to quantify, but think of downtown areas, especially in big cities like New York, Chicago, and San Francisco,” he said. “Neighborhoods with lots of small businesses have a certain vibrancy, and there are a lot of local jobs in those places. These are important. And that is definitely lost when we lose small businesses.”