Above: Student conducting research (Photo by Elena Zhukova)

Marcela Alfaro-Córdoba knew statistics could help scientists predict the effects of climate change, even though the disciplines of statistics and environmental science don’t seem related.

When she returned to her home country of Costa Rica following graduate school in the United States, she had come to understand that open-source data—readily available and shared information from researchers like herself—was a reliable and useful tool in moving progress forward. Yet, the now-UCSC assistant teaching professor saw a stark difference between the two countries in open accessibility to data and research—something she found concerning.

“As researchers and educators, we don’t only have a responsibility to open our findings, but also to make sure that people around the world have access to our findings as well,” she said.

With interest increasing over the last several years in making research results more accessible to the public, Alfaro-Córdoba can now access research from a vast number of agencies, universities, and nonprofits that have made their science “open.” In return, other researchers can see and use her research. And scientists like Alfaro-Córdoba have vastly more information available to them as they work to make discoveries, such as assessing the impact of climate change and weather on the environment, economy, and human health.

The Year of Open Science

Today, as more Americans seek ways to find updated research and data across scholarly topics, the federal administration wants to create more opportunities for accessing those important findings that, while largely publicly funded, are all too often inaccessible.

On January 11, 2023, President Joe Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris announced their administration’s next steps in committing to the Year of Open Science, with an emphasis on evidence-based decision making by way of the most well-regarded data and scientific findings.

This announcement included an updated guideline for how the federal government will advance these policies through 2023 and beyond, with a focus on accessible results for taxpayer-supported research, advancements in discovery and innovation, promoting public trust in the research and findings, and more equitable answers.

In the press release, the White House named the Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) as the leader for the efforts. The OSTP released prior memos during former President Barack Obama’s administration that this new, firmer guidance builds upon.

OSTP has been joined in this mission by at least a dozen other federal agencies, including the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s Transform to Open Science (TOPS) program, the U.S. Digital Corps, and the National Endowment for the Humanities.

While the announcement made waves in the nation’s capital, it provoked both cheers of glee and looks of confusion across the country’s higher education landscape.

Now, more than a year later, UCSC is part of the campaign to best implement the federal policies into academic futures and open scholarship for all.

Collaborative coordination

University Librarian Elizabeth Cowell hit the ground running when the White House made its announcement last January, with the tools she and her collaborators had been building on over the past few years. She also enlisted the help of open-science strategist Kristen Ratan.

Cowell has worked with a small but mighty team—Vice Chancellor of Information Technology Aisha Jackson and Vice Chancellor for Research John MacMillan—to coordinate the university’s unique plans for implementing the Year of Open Science. That effort included adjusting the name to “the Year of Open Scholarship,” adhering to the federal mandate to apply across all fields and federally funded research.

From left to right: University Librarian Elizabeth Cowell, Vice Chancellor of Information Technology Aisha Jackson, and Vice Chancellor for Research John MacMillan.

“We are uniquely positioned to do something here on this campus, because our three divisions [Library, Information Technology, and Research] are collaborative and working together,” Cowell said. “UCSC has deep commitments to open research and sharing just as a public good, so it makes those conversations way easier.”

Ratan came on board as a consultant for the plan’s implementation by way of Strategies for Open Science (Stratos), a nonprofit organization that works with open-science funders, advocates, open content, and infrastructure providers to produce tangible results toward open scholarship. From her experience (and also as the former publisher at the Public Library of Science), Ratan sees the collaborative partnership between the three divisions as a unique and fortunate tool for moving forward toward collective action.

“The campus itself is made up of a lot of people who are already excited and already practicing open research, so there’s a lot of groundswell toward not just acceptance, but also activity that we can rely on,” Ratan said.

Planning for rollout

With the new policies, said Cowell and Ratan, all publications and all articles are required to be made open access, and the underlying data needs to be free as well. The University of California had already put a groundbreaking policy in place dating back to 2013 for open access, but there is still a great deal of work that requires digitization.

After the White House’s announcement in January 2023, agencies were required to provide the OSTP with their initial plans for open-access implementation by August 2023. Now, research organizations like UCSC and other institutions are preparing for their implementation rollouts, with an effective start date of December 31, 2025.

One of the possible precipitating factors for the federal open-access mandate was likely the COVID-19 pandemic.

“During the global pandemic, researchers themselves started sharing their findings, without waiting for final publication—they set the career benefit that comes from formal publications aside for the public good,” said Ratan. “The new OSTP guidance codifies that early sharing and expands the requirement to all U.S. federal agencies.”

As Ratan explained, open-science funders originally moved their attention to providing open access to COVID-19 information, but soon thereafter also focused on the rapid dissemination of other information, including data and findings on urgent issues such as cancer and climate change.

Is it FAIR?

Benedict Paten, associate professor of biomolecular engineering and associate director of the Genomics Institute, shared that the White House’s announcement helps to promote responsible and reusable science, which has been a topic of conversation for many years at UCSC.

“For a long time, we’ve talked about open-source standards and the concept of FAIR—findable, accessible, interoperable, and reproducible,” he said. “Those are the four tenets that we want our data to abide by.”

Benedict Paten, associate professor of biomolecular engineering and associate director of the Genomics Institute (Photo by Carolyn Lagattuta)

As the methods to analyze and find data continue to get more complicated with machine learning and sophisticated algorithmic techniques, Paten said that it’s even more possible for errors or biases to make their way into the findings. As such, sharing results and data can be more effective in finding accurate results.

Paten and his team help run the Human Cell Atlas data platform, a collaborative effort to generate an atlas of all of the human body’s varied cell types. With the extensive volume of data, the team built a platform to make it easier for anyone to access that data and compute its findings.

“That’s a key part of building on collected data—that’s the idea; we’re at least trying to get as close to the ideal as possible,” he said.

After encountering barriers to open-source data in Costa Rica, Alfaro-Córdoba traveled to Italy and focused on open and responsible science as part of the International Theoretical Physics Centre. She aims to work toward advocacy and action in openly sourcing data and research for all through the new federal mandate.

“This is not only validation, but a hope that new generations of scientists can have a different mindset than previous generations, that the lessons we learned during COVID, the importance of sharing findings and sharing data, and the importance of data combined from different sources to create new knowledge—we can use those learnings to train a new generation,” she said.

Assessing the past and looking toward the future

Open science and scholarship is not a new concept at UC Santa Cruz.

In the summer of 2000, Professor David Haussler of UCSC’s Department of Biomolecular Engineering and then–graduate student Jim Kent (Kresge ’02, mathematics; M.A. ’86, mathematics; Ph.D. ’02, biology) worked doggedly to defy the odds to become the first in the world to assemble the DNA sequence of the human genome. Their accomplishments were recognized around the world, and led to the UCSC Genome Browser, a graphic web-based “microscope” for exploring the human genome sequence that is available free to anyone who wants it.

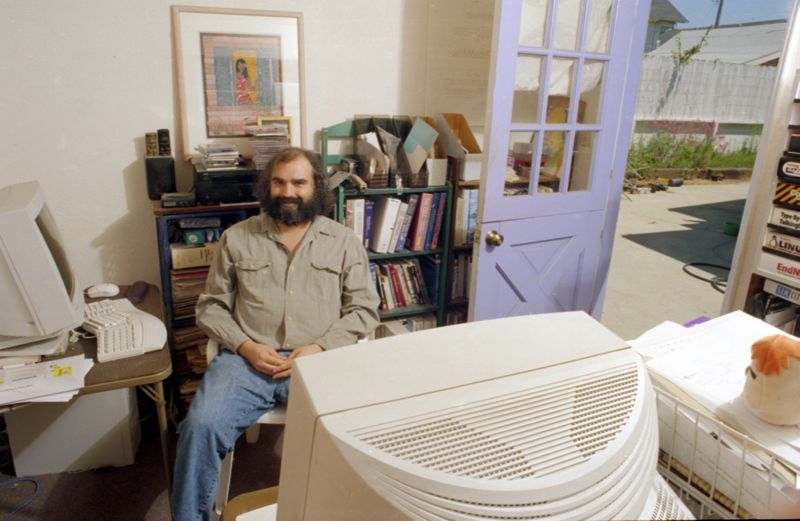

Jim Kent working in his home office on the human genome, circa 2000.

That work helped biomedical researchers delve into causes of disease and find new treatments, with about 20,000 researchers visiting the site per day.

In addition, in 2015, the university received a $3 million gift from alumnus Sage Weil (Ph.D. ’07, computer science), with a goal of supporting more research in open-source software. Two-thirds of the funding was provided for Adjunct Professor of Computer Science Carlos Maltzahn, who directed the Center for Research in Open Source Software at UCSC.

As Maltzahn told the UCSC News Center in 2015, “A lot of students build a significant amount of software infrastructure during their thesis research, and these contributions are often lost because there are no resources for students to continue working on their projects after they graduate.”

Ratan emphasized that point now, and clarified that those thoughts date back to the early 2000s with the launch of many digital journals.

“When that information becomes digital, there’s no reason to prevent others from accessing it anymore,” she said. “We’re not printing books and putting them on a truck, driving them someplace—there was a real groundswell of interest in making the world’s scientific information, in particular, freely available as a benefit to humanity.”

Ratan also emphasized that the research and findings are largely taxpayer funded.

“We’re paying for it, but we can’t access it … so that led to an open-access movement, which has been going on for over 20 years. This is really the people’s information.”