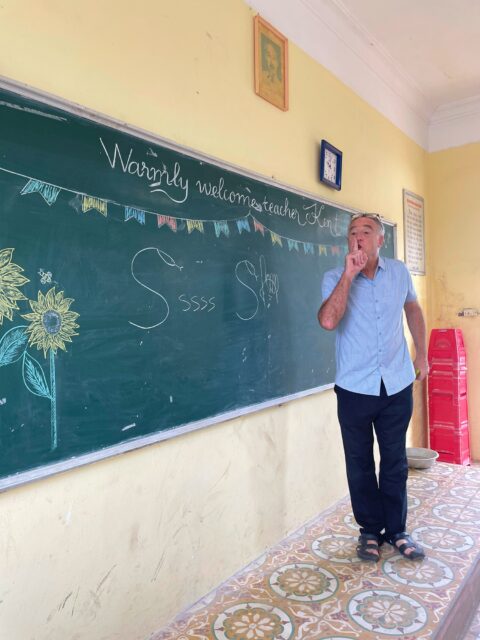

Above: Wallace teaches the full spectrum—grades K–12, as well as some adults.

I didn’t come to Vietnam to teach. I left the U.S. in 2018 to escape the dog-eat-dog and to find a place to write a novel. The teaching found me—in a Hanoi bar, of all places. I was approached by a young man seeking a tutor for his nieces and the children of his friends. Long story short: I was eventually offered, and accepted, a full-time position at an English center in Dien Chau (Nghe An Province). I’ve since moved to the beachside hamlet of Cua Lo (also in Nghe An), where I teach in public schools.

Becoming “official” required taking the TEFL (Teaching English as a Foreign Language) test for certification. The test was a snap.

English is taught in all Vietnamese schools, and their thirst for competency has them flocking to English centers around the country. Native English teachers are in high demand. What’s lacking are Americans—lots of Brits, Aussies, and South Africans. Ironically, the Vietnamese want U.S. English teachers. When students and adults find out I’m from the U.S. (Mỹ in Vietnamese), it’s often shouted in chorus, much to the dismay of the British-dialect-speaking crowd.

Wallace in his classroom

While most “foreign” teachers seem to coalesce in the major hubs (Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh), I find it vastly more rewarding—literally and altruistically—to teach in the rural areas. I don’t need the company, food, or culture of the West. I prefer to be immersed in the culture and people of Vietnam.

Everywhere I’ve traveled, people have been curious and respectful, asking about my life and American culture. They’ve been keen to have me experience their food, including frog, cricket, silkworm, and goat-blood pudding, and their traditions, like beating the ceremonial gong with a mallet or being invited to a giỗ—the anniversary celebration of a loved one’s death.

I was concerned about my reception when I first arrived in Vietnam because of the Vietnam War, wondering if lingering effects from the atrocities might sully my welcome. But the people I’ve spoken to harbor no ill will, and I’ve been able to have meaningful conversations, including with a North Vietnamese war veteran, that have deepened my understanding of the people, the country, and our shared history.

I’m frequently invited to homes for meals—even strangers extend offers. They’re genuinely overwhelmed by the novelty of an American in their land. That I am an English teacher makes me an honoree. They know the advantages, both at home and abroad, that this prized second language can offer—Vietnam is an emerging country in both global business and tourism.

As a writer/performing artist, I find the work rewarding. There’s lots of room to stray from the textbooks. For instance, I write stories for the kids. Stories they can relate to. Stories about children named Hoa and Minh. About fishing in streams in Do Luong or swimming at Cua Lo beach. The “mall” so many Americans know well becomes an open-aired market in these stories—every Vietnamese town has one. I insert motorbikes for cars, buses for undergrounds, bánh mì instead of burgers, treks to waterfalls rather than waterparks. And they adore the theatrics—the expressions, body language. So much of teaching language is theater, the art of communication. The young people eat it up, and they can get their heads around it.

While many English teachers in Vietnam coalesce in large cities such as Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh, Wallace says he prefers the rural areas and being immersed in the culture and people of the country.

Vietnam has taught me to breathe. To appreciate simplicity, smiles, and the joy of endless toasts amongst friends and strangers alike. It also happens to be a tropical paradise of waterfalls, beaches, rivers, and mountains.

You won’t get rich by coming here to teach English. But you’ll be enriched. Vietnam has a firm place in the American pathos. And this is not only a righteous path, but also one that may lead to discoveries and joys you never expected. I hope you’ll consider it.