Above: Bonnie Garmus (photo by Serena Bolton)

Banana Slugs who dive into Bonnie Garmus’s massively bestselling novel Lessons in Chemistry will feel their antennae zinging with a certain UCSC vibe.

Though it takes place in ’60s, the book takes a deep, scathing look at many of the issues today’s UC Santa Cruz students are still passionately concerned about: sexism, sexual harassment, social inequality, and underrepresentation in the STEM fields.

That Slug-conscious feeling is no coincidence. Garmus (Rachel Carson ’79, aesthetic studies/creative writing) was a UCSC student during an era of political foment.

“In 1979, the women’s movement, led by Shirley Chisholm and Gloria Steinem, was in full swing,” Garmus said during a brief moment of repose in the midst of her book-promoting responsibilities. “I really looked up to them as well as Angela Davis [Distinguished Professor Emerita, history of consciousness and feminist studies], who spoke at my graduation. These women and plenty of others were crafting a revolution that sought to put an end to inequality in all forms.”

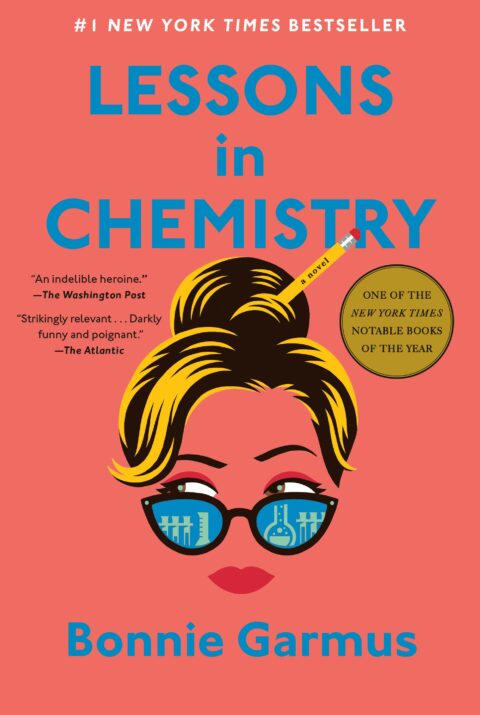

Lessons in Chemistry introduces the unforgettable character Elizabeth Zott—a scientist in the early 1960s and a woman with a mind of her own.

When she’s fired from her job for being unwed and pregnant, she can’t make ends meet. So, despite severe reservations, she accepts a job as a TV cooking-show host. What she doesn’t accept is the image her producers want her to project. Instead, Zott sets out to teach her audience of housewives that cooking is chemistry—igniting a revolution.

The novel—wickedly funny while edged with a sharp chef’s knife of subversion—was among the 20 bestselling new books of 2022 and was named Best Book of the Year by the New York Times, Washington Post, NPR, Oprah Daily, Entertainment Weekly, and Newsweek. Apple TV+ is producing a series due to debut this year, starring and executive-produced by Academy Award–winning actor Brie Larson.

‘Question Authority’

“I will say that UCSC itself had a certain spirit of change—of fearlessness—that definitely made a huge impression on me,” Garmus said. “Back then nearly everyone seemed to have a bumper sticker that read, ‘Question Authority.’ I loved it and still do, probably because it sounded radical to me.”

But in a sentiment that reflects an Elizabeth Zott–like pragmatism, Garmus says that pushing back on the powers-that-be is just rational.

“The truth is, questioning authority isn’t radical—it’s sensible,” Garmus said. “People get put in positions of power through various means—elections, inheritance, luck, being louder than others, so questioning authority is still critical, as is questioning the motives that drive that authority.”

Garmus was able to work a lot of that indomitable, questioning spirit into an immensely popular book.

“It’s really something to be on bestseller lists around the world; to win honors like Book of the Year in multiple countries; to see the book sitting on my shelf in 40 different languages; to listen to readers tell me how it’s impacted their lives for the better, and to be part of new dialogues about feminism,” said Garmus, who was 64 when the novel debuted last year. “And then, on top of that, to watch Aggregate Films and Apple TV+ turn it into a series …. Some days I wake up and say, ‘really?’”

The long road to a runaway success

It’s not hard to understand Lessons in Chemistry’s mass appeal. Garmus’s deftly written book is often hilarious but it’s also heartbreaking and unsparing in the way it describes the abuses Zott suffers at the hands of various mediocre and justifiably insecure male employers.

Zott’s ascent through the realms of science is anything but linear. Garmus’s rise to the top of the bestseller list is also full of side trails.

In fact, Garmus, who grew up in Riverside, Calif., transferred to UCSC after two years at Kenyon College in Ohio because she was seeking an education that was, in her words, “less linear. I was interested in lots of subjects; Santa Cruz supported that. As for UCSC fostering an adventurous spirit, I already had one so it felt like a good match for me.”

After graduating from UCSC, Garmus worked for a company that published science books. Later she tried her hand at writing computer manuals. After giving up that work, which she found tedious, Garmus established herself as a copywriter in Seattle, focusing on science and tech.

The position forced her to be a generalist, delving deeply into many fields, representing her subjects accurately, and figuring out ways to spark interest in those various topics. Those skills proved invaluable when she started writing fiction. Her work also provided her with a memorable negative incident that gave her the first creative and emotional spark for Lessons in Chemistry. “I’d been on the receiving end of some pretty blatant sexism, and although that wasn’t new to me, it was the inefficiency and sheer ignorance that drives sexism—the pettiness; the way it wastes time and talent—that really hit me that day,” Garmus said. “I started thinking about women in every corner of the world; about how much of their time and talent had also been wasted—and not just on that particular day, but that year, decade, era, throughout history. “And so,” Garmus continued, “I started that first chapter.”

The catalyst for a revolution