This article is adapted from a longer online special report that includes videos and more content. To see the full report, visit reports.news.ucsc.edu/ethics-bowl. And, for more information, visit publicphilosophy.ucsc.edu.

Twice a month from last September to February, UC Santa Cruz philosophy lecturer Kyle Robertson woke up early, dropped his kids off at school, drove north for one hour and fifty minutes, crossed the Richmond Bridge, and went to San Quentin State Prison.

Above: San Quentin State Prison Warden Ronald Davis observes at an Ethics Bowl debate at the prison. Photo by Jonathan Chiu, San Quentin News

He was there to teach a course in Ethics Bowl—a nonconfrontational alternative to the traditional competitive form of debate—in collaboration with the Prison University Project (PUP).

At the same time, he was also teaching an undergraduate course and coaching a team in Ethics Bowl at UC Santa Cruz.

He soon suggested and arranged a very unusual debate between seven philosophy students from UC Santa Cruz and a team of prison inmates from San Quentin. It took place in the prison chapel—in front of an audience of nearly 100 inmates.

“This is the first time there’s been a debate inside San Quentin,” says Robertson, who served as moderator. “And it’s one of the first Ethics Bowls that’s ever happened in a prison.”

The event at San Quentin is just one of the many outreach activities of the Center for Public Philosophy (CPP) at UC Santa Cruz. Founded in 2015 by associate professor of philosophy Jon Ellis, it is supported by the Humanities Institute, an incubator for humanities research on the Santa Cruz campus.

The center is also coaching and conducting regional Ethics Bowls for high schools throughout Northern California; creating short animated videos about philosophical problems that teach reasoning skills and how to avoid biased thinking; teaching moral philosophy and ethics in Santa Cruz jails; working with biologists to study how language affects conservation efforts; and even introducing philosophy, ethics, and critical thinking to children at three elementary schools in the local community.

The idea is to move philosophy away from the stereotype of the old bearded man pondering in the mountains and instead apply its principles to crucial problems we all face in today’s world. And in an era of intense partisanship, rabid fighting on social media, “fake news,” and “alternative facts,” the center promotes a new normal of how to talk about the really big issues confronting us today—in a civilized, rational, and much friendlier manner.

Constructive debate

Ethics Bowl is the opposite of traditional forms of debate in this country—the “win-at-all-costs,” negative, whatever-it-takes debate that is typical of cable news, congressional debates, election campaigns, and our courtrooms. Both Ellis and Robertson believe that traditional debate competitions, a well-established part of the U.S. high school curriculum since early in the 20th century, ultimately strengthen and reward one-sided thinking.

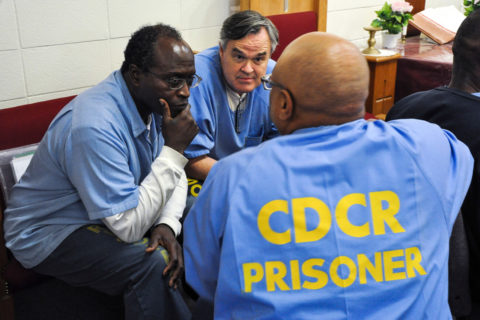

Above: San Quentin State Prison inmates Forrest Lee Jones (left), Wayne Boatwright (center), and Nelson Butler talk at an Ethics Bowl debate at San Quentin. Photo by Jonathan Chiu, San Quentin News

“I think that the way we argue in courts of law, and in ‘forensic’ debate competitions, has undermined our ability to engage in the constructive debate that is necessary for democracy to function. Ethics Bowl, or something like it, could be a cure,” says Robertson, assistant director of the CPP, who earned a law degree from UC Berkeley and practiced for two years in Silicon Valley before earning a Ph.D. in philosophy from UC Santa Cruz in 2015.

“Standard debate is reasoning with an agenda,” adds Ellis. “It is also what we find so corrosive in today’s politics. People have their favored view and then emphasize the information that fortifies their stance. Evidence that threatens their position is rationalized away, while problems for the opposing view are scavenged for, and then magnified.

“Not surprisingly, schools and communities around the country are pursuing alternative forms of debate, ones that switch the order of priority, and set the goal of truth and understanding over the goal of persuasion.”

Excitement and anxiety

Robertson’s two-hour class for the Ethics Bowl debate at San Quentin covered topics such as moral theory and how to use ethics to justify a position in a case.

“They loved it—they were really into it,” says Robertson of the inmates. “They would stay after class to talk to me; they would not want to stop talking,” he adds. “They read incessantly and were really well-prepared. I think also, pragmatically, they were learning moral advocacy skills for their own hearings—many have life sentences with a possibility of parole.”

But for the UC Santa Cruz students, training for the debate was a mixture of anxiety and adrenaline.

As philosophy major Anna Feygin (Oakes ’18) notes, “It’s one thing to be forewarned about what to expect when you head inside a prison; it’s another to actually experience it.

“I was nervous because I was essentially going and walking into a prison, but excited at the same time,” she recalls. “I’d never been to a prison—let alone talked to a prisoner, or an ex-prisoner—so it was pretty nerve-wracking at some points.”

Third-year philosophy student Pedro Enriquez (Oakes ‘19) also had some concerns.

“I thought it was going to be a lot more like the movies where they’re locked down, and you know, they’re going to be hollering or whatever,” he said. “So when we walked in after we passed the security and they were just walking around, I was like, ‘Wait, is anybody gonna do anything, like where are all the cops, what if they do something?’”

But their fears were soon alleviated.

“Once the prisoners started coming up and talking to us, they were really friendly,” says Enriquez. “And I remember looking out into the crowd and seeing the inmates and how attentive they were, and seeing all the volunteers and just thinking, ‘Wow, this is a big deal.’ You know, it’s easy for me to think of this as an extracurricular activity, but it means a lot more than that to a lot of people.”

Inmates’ experiences

The Ethics Bowl class and subsequent debate with UC Santa Cruz philosophy undergraduates affected the inmate participants in a variety of ways. Each had a personal reason for taking part in the debate, and afterward, most expressed a desire to participate in future Ethics Bowl debates.

“I decided that it would be a great idea and learning experience to engage other students in some type of formal debate,” says inmate Randy Akins. “Just to be able to interact with the public made me feel whole again.

Above: David Donley (top row, center), philosophy Ph.D. candidate, with Santa Cruz County Jail inmates.

“I’ll do it again,” he adds. “I learned how to incorporate other people’s views into a cogent argument.”

Inmate Forrest Lee Jones had a different take on the experience.

“I wanted to represent my team and demonstrate the knowledge I’ve been learning in the Prison University Project classes,” says Jones. “I’d never participated in a debate and wanted to experience its setting.

“Coming into this Ethics Bowl class and debate, I struggled in the understanding of the concepts of ethics,” Jones adds. “But doing the exercise of applying them to real-life events has helped me better understand them. They are not some abstract concepts, but relevant and applicable in solving life’s problems.”

Thinking and reasoning

There’s no shortage of contentious topics that can be debated in an Ethics Bowl—ranging from the Trump Administration’s “Muslim Ban,” to the use of military drones, to political discussion on social media, to the ethics of marital infidelity.

At San Quentin, the students and prisoners grappled with just two cases: “Should we change a rule made by the American Psychiatric Association that states it is unethical for psychiatrists to give a professional opinion about public figures they have not examined in person?” (a rule that has recently generated public debate because of President Donald Trump), and “Is it ethical to boycott, divest, and sanction Israel for its actions in the West Bank and Gaza Strip?”

But perhaps the most stirring thing for UC Santa Cruz philosophy professor Jon Ellis was how genuinely excited the inmates in the audience were by the excellent job the San Quentin team was doing at this particular exercise of fair-minded reasoning and open-minded listening.

“There was an integrity there that really stood out to me, in the way that both teams—but especially the San Quentin team—engaged with the questions that were posed, showing a sincere respect for the complexities of the thinking and reasoning required by the difficulty of the issues,” says Ellis.

“I was no less impressed by the UC Santa Cruz team,” he adds. “What was most impressive to me was the poise and goodwill the students showed after losing the debate to the inmate team. If there was bitterness or disappointment, it didn’t come through at all; rather, directly after the event, they were genuinely and eagerly debriefing with the inmates, exchanging ideas, perspectives, and appreciation.”

Robertson says that he plans to co-teach a class this year with the Prison University Project at San Quentin, and that together they hope to hold future Ethics Bowls at San Quentin involving up to four new prison teams. He adds that the Center for Public Philosophy is also hoping to expand its outreach locally and host the first-ever Ethics Bowl in the Santa Cruz County jail system.

“This type of event embodies the type of activity I value at the center for a variety of reasons,” says Robertson. “It reaches out to communities that are generally not included in our public deliberations about difficult ethical and political situations. The San Quentin inmates are often the objects of such deliberation, but rarely, if ever, participants.

“It also teaches students much more about what they believe, and why they believe it, than a traditional ethics classroom experience,” he adds. “This pushes them, I think, to make arguments that they themselves believe in rather than trying to predict what others want to hear.”