Above: UCSC student Liam Asayag posing with a DJI Mavic 2 Pro drone on campus. This drone, used as a prop for the photo, has a similar camera to the drone model Asayag designed for humanitarian use in the war zone of Ukraine. (Photo by Carolyn Lagattuta)

Liam Asayag never thought he’d be part of a war effort. Nor had he ever built—or even considered making—a drone.

But, motivated by his mother, who is active in international relief work, and assisted by a UC Santa Cruz robotics lab, the junior robotics student (Porter ’24) has done exactly that by designing a drone that can help in search-and-rescue work in Ukraine.

He has never taken on this type of project before. But with funding available from donors who worked with his mother’s organization, he thought he would try.

“I’ve never built a drone, period,” he said. “It was a really, really steep learning curve.”

It was also a new experience for Steve McGuire, assistant professor of electrical and computer engineering. He had never had a student work on a similar project.

“It’s not every day you have an undergrad show up at your door with a six-figure budget asking to use your space,” he said.

An entry into relief work

Asayag, 20, grew up in Fort Lauderdale, Fla., where he was on a championship robotics team. He came to UC Santa Cruz because he fell in love with the campus and was interested in going to college outside of his home state.

His new endeavor into relief work began last spring when he learned that his mother, Shelly Tygielski, was planning a trip into the Ukraine war zone.

“I was worried about my mom and I didn’t want her to go alone,” he said.

Tygielski had left the corporate world to become a meditation teacher and a community organizer. In March 2020, she founded the Pandemic of Love movement, which started as a way to connect people who needed assistance during the COVID-19 pandemic directly with those wanting to help. The organization has gone on to partner with a variety of social justice and humanitarian groups around the world. Tygielski also serves on the board of Global Empowerment Mission.

During spring break, Asayag got on a plane with her to Europe. Seeing the devastation was an experience he will never forget. Thousands were crossing the border from Ukraine to Poland.

“A lot of them were walking—some five to six days—with little kids, as well,” Asayag said. “It was really heartbreaking to see.”

Seeds of an idea

Asayag also set up Starlink satellites for the schools and at community centers, as well as a huge solar panel in a children’s hospital in the capital of Moldova, which serves as a backup for when the power goes out.

In a tour of the area, he and his mother met some search-and-rescue teams who were providing medical equipment and other supplies. Asayag wondered what the teams did if they couldn’t physically get to a village to offer help. They said they just didn’t go and had no other way to get the supplies through.

Asayag found out later people had tried to use drones to deliver supplies, but they had been shot down. At a cost of $50,000–$100,000 each, the drones were far too expensive to keep sending out. Though he had never built a drone before, he did some research and began seeking information while they were still in Ukraine, and he thought he could probably build one for $2,000.

When he got back home, he wrote a proposal to ask for money from some of his mother’s bigger donors to seed the project.

“There were no guarantees that it would be a success or that it would make a difference,” Tygielski said. But Asayag convinced the donors that the project was worth pursuing.

The next step was to get a place to work on the project. Asayag approached McGuire, whom he had met in a class.

“At first I was timid,” Asayag said. “But Professor Steve is a nice guy. I wrote him a long and detailed email. He replied ‘Sure, I’d love to help. Do independent research in my lab if you need the space.’”

Asayag immediately jumped into the project, spending several hours a day researching in the library and working in the lab.

“It was 0 to 100,” he said. “After class, I went to the lab.”

Research, listening, learning

Because of his inexperience, it was difficult to know how to proceed, and there were many twists and turns in the process.

“There was a lot of research to be done, a lot of listening, a lot of getting advice from others,” Asayag said.

He said he appreciated the advice he got from McGuire’s other students who had worked with drones. They freely shared their knowledge about what does and doesn’t work.

UCSC student Liam Asayag (left) with Steve McGuire, assistant professor of electrical and computer engineering, who provide Asayag with lab space to do independent research. (Photo by Carolyn Lagattuta)

The project changed several times over the ensuing weeks. Initially, the idea was to build a drone that could carry 12 pounds of medical or other supplies and drop it with a parachute into a village that needs help. But the project evolved instead to building a reconnaissance drone that would take video footage of newly bombed areas so that search-and-rescue workers could see in advance if the area was safe to access and what routes could be used in the aftermath.

Asayag described the drone as “pretty much a miniature airplane” that is able to fly up to 40 kilometers out and back at a top speed of 200–220 km per hour.

After finals were over, Asayag said he went to McGuire’s lab almost every day.

“Some days I would be there from 11 a.m. to 1 a.m.,” he said. “I had access even if no one was in there.”

Project success

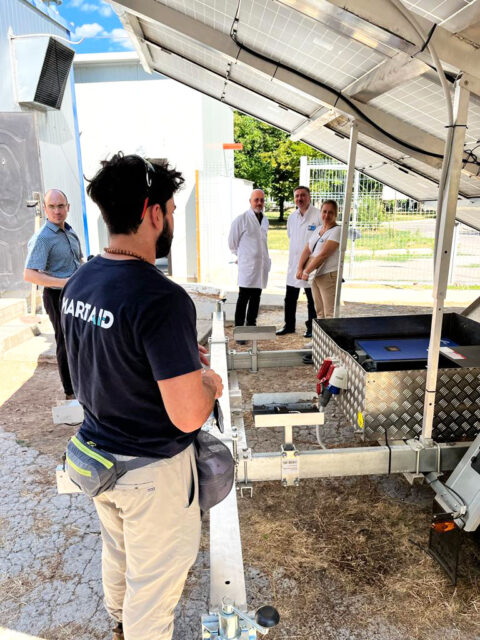

Asayag thought he had until September to build his prototype, but he later found out it had to be completed by July, when he needed to transport it to Ukraine to show it to SmartAID International, the relief organization he was working with.

“The last week or so before leaving for Ukraine, I was scrambling,” he said. “The drone that I was test flying crashed five days before I had to leave.”

He ended up having to buy new parts at the last minute and reconstruct it.

“Thank God for Amazon Prime,” he said. “We got the parts in two days.”

Fortunately, the project was a success, and the organization he was working with liked it. The drone Asayag designed will be built in a “Fab Lab,” a small workshop offering digital fabrication at a university located in Lviv, Ukraine. His initial estimate of cost turned out to be correct: The base drone costs $1,500, and then there are some extra costs for things like various cameras.

Asayag’s drones will be used by local aid groups and volunteers on the front lines, said Shachar Zahavi, founding director of SmartAID.

Drones are a game changer for aid workers.

“In humanitarian aid, the only alternative to drones is motorbikes, bicycles, and foot,” Zahavi said. “Drones simplify things and have a real impact on our work and decision making when it comes to reaching remote and dangerous areas.”

Zahavi was happy when Asayag stepped forward to help.

“Liam was amazing to work with and still is,” he said. “He is committed to helping SmartAID build a network that would help not only us but also our local aid partners and groups of volunteers to do their work in a safe and more secure way.”

Teaching students to be world citizens

Liam Asayag, left, talks with a displaced Ukrainian woman. Asayag and his mother, Shelly Tygielski, who runs a global mutual aid organization, went on an aid mission to Ukraine. While they were there, Liam connected with their partners SmartAid and a private military group that is helping with search and rescue, extractions, reconnaissance, and deliveries.

McGuire, the UC Santa Cruz assistant professor Asayag worked with, is a former Marine pilot who has served in Iraq and understands what it means to be in a war zone. He is glad he could help out with the project.

“Certainly, I want to encourage my students to do things that make a difference, whatever that means to them,” he said. “I want to make sure we teach students to be world citizens. We don’t just work in isolation.”

His open-minded attitude really impressed Asayag’s mother.

“He is a great example of a nurturing professor that can really inspire their students to do great things,” she said.

Asayag’s interest in relief work hasn’t stopped with the drones. While in Ukraine, he also assisted with SmartAID’s effort to set up “smart classrooms” in Poland, Ukraine, and Moldova for displaced Ukrainian refugees. The classrooms allow students to connect with teachers and students from their home country through Starlink, a satellite internet service operated by SpaceX. Asayag also helped a hospital in Moldova get a solar panel generator that pumps air into tanks for patients at the hospital.

Asayag hopes to eventually get his master’s degree and see where his research takes him. He would like to continue doing volunteer work.

“There’s no shortage of disaster zones,” he said. “I’ve learned that over the last year. There are always volunteers needed everywhere.”

His mother couldn’t be prouder.

She hopes Asayag’s story will serve as an inspiration to other freshmen and sophomores who wonder how much they can contribute when they don’t yet have a degree or many resources.

“If you have the perseverance and vision, you can create the connection. You first need to have the belief in yourself that you can do it,” she said. “I hope this will inspire students to understand that they don’t have to wait until they graduate to do something great in the world. They can solve real problems today.”