Breakthrough of a lifetime

Harry Noller, the Sinsheimer Professor of Molecular Biology at UC Santa Cruz, was the winner of a $3 million Breakthrough Prize in Life Sciences for revealing how the complex molecular machines called ribosomes translate genetic code and build the proteins in all living cells.

The award was presented at a star-studded ceremony in December hosted by Academy Award–winning actor Morgan Freeman at the NASA Ames Research Center in Silicon Valley.

The Breakthrough Prizes were founded in 2013 by Silicon Valley entrepreneurs Sergey Brin and Anne Wojcicki, Mark Zuckerberg and Priscilla Chan, and Yuri and Julia Milner.

Harry F. Noller, left, director of the Center for Molecular Biology of RNA, Robert L. Sinsheimer Prof. of Molecular Biology and Professor Emeritus of MCD Biology at the University of California, Santa Cruz, is interviewed on the red carpet before the Breakthrough Prize at Moffett Airfield in Mountain View, CA, on Sunday, Dec. 4, 2016. (Photo: Noller, used with permission of Bay Area News Group © 2017. All rights reserved)

“Harry Noller has performed a tour de force in molecular biology for the past 50 years,” said UC Santa Cruz Chancellor George Blumenthal. “This recognition is well-deserved.”

Noller’s research group was the first to solve the complete structure of a ribosome, publishing landmark papers in 1999 and 2001. More recent work in his lab has shown how the ribosome actually works to carry out protein synthesis. This research has practical applications because many antibiotics work by blocking the activity of bacterial ribosomes. Understanding the structure of the ribosome has enabled the development of novel antibiotics that hold promise for use against germs that have developed resistance to current drugs.

Noller’s discoveries also shed light on fundamental questions about the origins of life. Ribosomes are ancient structures that provide the link between the genetic instructions encoded in DNA and RNA molecules and the proteins that carry out most of the activities of living cells.

Each ribosome is composed of both proteins and RNA molecules interlaced together. When Noller first proposed in the 1970s that the RNA component performs the ribosome’s key functions, the idea met stiff resistance because only proteins were thought capable of catalyzing biochemical reactions. But he turned out to be right.

“This was a huge paradigm shift. It turned our understanding of molecular biology upside down,” said Noller, a professor emeritus of molecular, cell and developmental biology.

For more information about Harry Noller and the Breakthrough Prize, see reports.news.ucsc.edu/breakthrough.

Pedestrian paradise?

Imagine an urban neighborhood where most of the cars drive themselves. What would it be like to be a pedestrian?

Actually, pretty good, according to Adam Millard-Ball, assistant professor of environmental studies. In fact, pedestrians might end up with the run of the place.

In his study, “Pedestrians, Autonomous Vehicles and Cities,” Millard-Ball looks at the prospect of urban areas where a majority of vehicles are “autonomous” or self-driving. It’s a phenomenon that’s not as far off as one might think.

“Autonomous vehicles have the potential to transform travel behavior,” Millard-Ball says. He uses game theory to analyze the interactions between pedestrians and self-driving vehicles, with a focus on yielding at crosswalks.

Because autonomous vehicles are by design risk-averse, Millard-Ball’s model suggests that pedestrians will be able to act with impunity, and he thinks autonomous vehicles may facilitate a shift toward pedestrian-oriented urban neighborhoods. However, Millard-Ball also finds that the adoption of autonomous vehicles may be hampered by their strategic disadvantage that slows them down in urban traffic.

Ocean’s impression

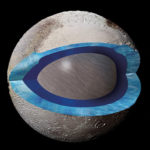

This cutaway image of Pluto shows a section through the area of Sputnik Planitia, with dark blue representing a subsurface ocean and light blue for the frozen crust.

A liquid ocean lying deep beneath Pluto’s frozen surface is the best explanation for features revealed by NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft, according to a new analysis. The idea that Pluto has a subsurface ocean is not new, but the study provides the most detailed investigation yet of its likely role in the evolution of key features such as the vast, low-lying plain known as Sputnik Planitia.

Sputnik Planitia, which forms one side of the famous heart-shaped feature seen in the first New Horizons images, is suspiciously well-aligned with Pluto’s tidal axis. The likelihood that this is just a coincidence is only 5 percent, so the alignment suggests that extra mass in that location interacted with tidal forces between Pluto and its moon Charon to reorient Pluto, putting Sputnik Planitia directly opposite the side-facing Charon. But a deep basin seems unlikely to provide the extra mass needed to cause that kind of reorientation.

“It’s a big, elliptical hole in the ground, so the extra weight must be hiding somewhere beneath the surface. And an ocean is a natural way to get that,” said Francis Nimmo, professor of Earth and planetary sciences.

Help for English learners

Peggy Estrada, an associate research scientist in Latin American and Latino studies, has been awarded a three-year, $999,999 grant to study how to best help school-age English learners achieve English-language proficiency and academic excellence.

Estrada said 43 percent of California K–12 students have a primary language at home other than English. Students who do not score English proficient on a state test when they enter school are classified as English learners. Nationwide, they are the fastest-growing proportion of public school enrollment.

The grant is a Lyle Spencer Research Award from the Spencer Foundation. With it, Estrada and colleagues Timea Farkas, an assistant research scientist in Latin American and Latino studies, and Claude Goldenberg, professor of education at Stanford University, plan to conduct a small-scale experiment involving 16 schools in a large California school district, one of the biggest in the country with a large population of English-learning students.

Rising up the rankings

UC Santa Cruz is among the top 50 universities in the world, according to the U.S. News & World Report 2017 Best Global Universities rankings.

UC Santa Cruz tied for No. 27, the fifth-highest University of California campus. The rankings evaluate 1,000 universities in 65 countries across 12 indicators, including global and regional research reputation, publications, citations, and international collaboration.

The campus has continued to increase its ranking, even as the number of universities reviewed has expanded. Last year, UC Santa Cruz came in at No. 48 (out of 750 universities), and No. 63 (out of 500 universities) in 2015.

Sounding them out

UC Santa Cruz music professor David Dunn listening to bark beetles.

UC Santa Cruz music professor David Dunn has joined forces with two forest scientists from Northern Arizona University to combat an insect infestation that is killing millions of trees throughout the West.

They are applying the results of nearly a decade of acoustic research in an unconventional collaborative effort to stop bark beetles from tunneling through the living tissue of weakened, drought-stressed pine trees.

The trio has now received a patent for a device that uses sound as a targeted sonic weapon to disrupt the feeding, communication, reproduction, and various other essential behaviors of the insects.

“When massive tree death started occurring in northern New Mexico where I was living, I became curious if there were sounds associated with such a large amount of biological activity,” said Dunn.

Dunn thought about how to listen to the interior of trees and came up with a simple listening device that cost less than $10 to build. Designing unique and inexpensive devices in order to listen to sound had long been a part of his artistic work.

Guardian of the sacred

Raymond LeBeau (Stevenson ‘18, environmental studies, philosophy minor), who won a $10,000 scholarship, plans to earn a Ph.D. in order to help tribal communities with environmental and land-use issues.

For Raymond LeBeau and other members of the Pit River tribe, Medicine Lake in northeastern California is a sacred site, a place of healing.

But for the Bureau of Land Management and the Calpine energy company, the serene patch of blue that sits amid a volcanic landscape was a promising geothermal energy site. For more than 30 years, the Pit River tribe—including the young LeBeau and his family—protested the proposal, and, last year, a court ruled the energy-company leases had been made without proper environmental review or tribal consultation.

“That (the prolonged fight) was what influenced me,” said LeBeau, 20, who is a member of the Illmawi Band of the Pit River Nation. The experience, he said, “really pushed me to say I want to stop that.”

Recently, LeBeau (Stevenson ‘18, environmental studies) was given a $10,000 award as part of the Morongo Band of Mission Indians’ Rodney T. Mathews Jr. scholarship program. His plan is to earn a Ph.D. in order to help tribal communities with environmental and land-use issues.

A novel concept

In What Becomes Us, a new novel by UC Santa Cruz literature professor Micah Perks, twin fetuses tell the story of a pregnant woman who abandons her controlling husband in Santa Cruz, moves to a small upstate New York town, falls in love with a Chilean man, and becomes obsessed with a historical figure who wrote one of the first captivity narratives about survival in the wilderness.

The longtime codirector of the UC Santa Cruz Creative Writing Program explained how she came up with the idea of having twin fetuses narrate the story.

“I originally wanted a big storytelling voice, but I didn’t want the voice to be anonymous,” Perks recalled. “I liked the idea of this big, Whitmanesque voice coming from a tiny being inside the main character—a little like the position of the author.”

“I love twins, and I love all the utopian possibilities with twins,” she added. “And the ‘we’ voice now seems essential to what the book is about: the tension between individual desires and the desire for community.”

Doing the math

A pilot program in online adaptive learning at UC Santa Cruz has led to higher placement in math courses for newly admitted freshman students—and a commitment to instruct students in math in ways that adapt to their own proficiencies.

Of the more than 722 entering students who completed math placement via online assessment during the summer of 2015 and made use of adaptive learning software to review and reassess, 84 percent showed marked improvement that enabled them to qualify for higher math courses.

Many students who had placed into College Algebra (Math 2), for example, were placed into Precalculus (Math 3) or Calculus after working through online adaptive instruction. Others who had initially placed into more advanced courses than College Algebra also improved their placement, enabling them to make more rapid progress toward their academic goals. All of this was accomplished without worsening overall pass rates in these courses.

Reef madness

Margaret Wertheim in the Föhr Reef, Museum Kunst der Westküste, Föhr, Germany, 2012.

Yarn has come alive at UC Santa Cruz with the visit of a traveling sculpture exhibit called Crochet Coral Reef: CO2CA-CO2LA Ocean, a world-renowned art and science project by Margaret and Christine Wertheim of the Institute For Figuring.

The exhibition, on view at the Mary Porter Sesnon Art Gallery until May 6, 2017, responds to the environmental crisis of global warming and the escalating problem of oceanic plastic trash.

Residing at the intersection of mathematics, marine biology, handicraft, and community art practice, Crochet Coral Reef: CO2CA-CO2LA Ocean highlights not only the damage humans do to the Earth’s environment, but also our power for positive action.

In addition, UC Santa Cruz students and community members are busily crocheting the UC Santa Cruz Satellite Reef as part of the Crochet Coral Reef project’s worldwide reefing effort, one of the largest participatory science and art endeavors

in the world.

The UC Santa Cruz Satellite Reef will be exhibited at the Seymour Marine Discovery Center starting May 4, 2017.

Both Crochet Coral Reef: CO2CA-CO2LA Ocean and the UC Santa Cruz Satellite Reef are sponsored by the Institute of the Arts and Sciences, part of the UC Santa Cruz Arts Division.